Paper to Praxis: Informal Growing, Stewardship & Bloordale Beach Community Gardens

By Laura Lebel-Pantazopoulos, Junior Planner at SpruceLab

Paper

As a recent Master of Planning graduate, I’m really pleased to have been awarded last month with the Minto Planning for Sustainability: Best MRP Award for the best Major Research Paper related to sustainability. This paper, researched and written from home in the height of the pandemic, was a bit outside the box when it comes to urban planning research. I worked hard to make it practical, and I'm grateful to have been recognized and supported by Ryerson University’s (renaming in process) School of Urban and Regional Planning faculty for exploring the role that community members play in caring for plants and the earth on public land (without permission).

My MRP investigated the topic of informal growing and stewardship* on public land in Toronto. Activities like these are sometimes called ‘guerrilla gardening’, but this term was too limiting for the range of relationships and work being done on the land by the people who I interviewed. Whether it be through the management and removal of non-native species, growing food, ceremonial use of plants and land, restoration work, earth work, or maintaining ornamental gardens, the people who I interviewed all took it upon themselves to connect with and alter the plants and earth in public places, with purpose and without permission. It was fascinating to talk with these informal growers and the public landowners, and determine where their goals aligned and conflicted. Based on these observations, I created a tool to assist in developing mutually beneficial agreements between informal growers and public landowners to leverage the connection and interest of these community members, and meet goals of well-being, ecological resilience, and community building.

Check out the paper here.

A video explanation of my research topic.

*The term ‘stewardship’ has associations with Indigenous Land Stewardship, which has been ongoing on the land discussed in this research since time immemorial, and is rooted in Indigenous ways of being on and understanding the land. For the purposes of this research, stewardship was used in a broader sense for anyone who seeks to care for the land.

Praxis

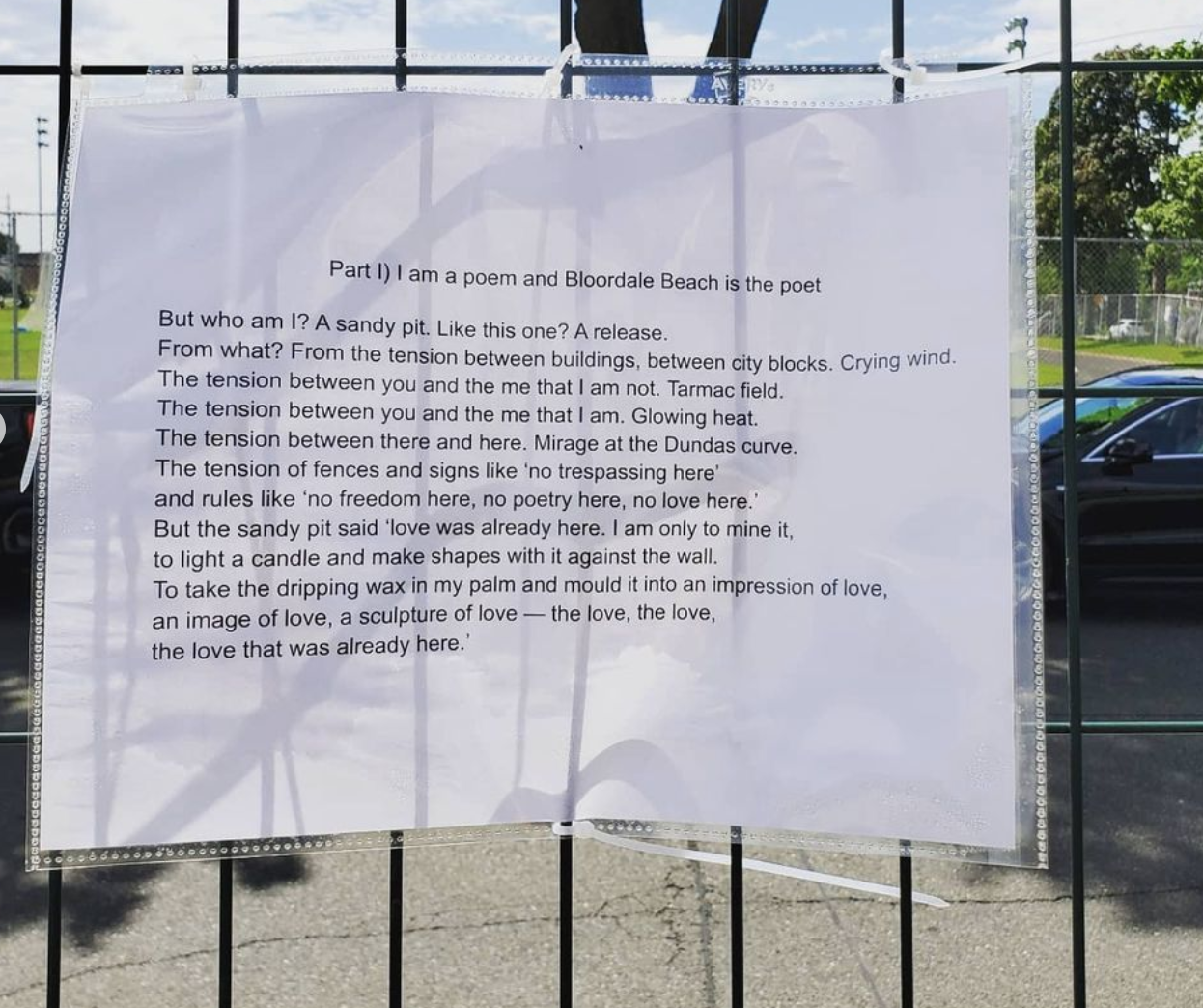

After sharing this paper online in April, the person behind a public rotary dial phone on Bloor St W, who was looking to encourage some local garden plots, reached out to me on Twitter, asking if I knew anyone who would be interested in creating an informal garden at Bloordale Beach. Bloordale Beach was an inactive construction site in the west end of Toronto (and “totally a real beach”), owned by the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), which was reclaimed repeatedly by the community as a path and public space from 2019-2021. Signs declaring the space a UNESCO World Heritage Site, warning to watch for sharks, and more, made this place a hilarious addition to the community, and the persistent and illegal reopening of the construction fences (even despite the security guards hired at one point) made it a valuable informal public space, especially during the pandemic. Bloordale Beach was featured on the Spacing Podcast and in numerous articles. By chance, I happened to live several blocks from this space, and inspired by the great people who I interviewed for my research, and the online request, I decided to take the initiative. One morning in May, I scoped out the soil quality of the space which I had passed by countless times before, self-consciously carrying a shovel, and went for it.

Bloordale Beach sign (www.sharikasman.com/bloordalebeach)

With a few printed posters and social media posts, the Bloordale Beach Community Gardens began, and they became bigger and drew in more people than I ever imagined. Soon, around 10 people were coming every week, and even with all the additional beds we created, there was often not enough work to go around. A local community member allowed access to their water and wagon to carry water to the site (our biggest obstacle), we received donations from community members and the local garden centre, and passersby would compliment the garden and encourage us almost every time we were out. In line with the informal nature of the entire space, I encouraged everyone to make their own plots if they wish (only one person took me up on that), and everyone participated in the decision making. A stranger online had given me ‘permission’, I took initiative, and then the community made the rest happen.

At one point, I took a risk and reached out to the TDSB about a place-making grant for Bloordale Beach and the gardens, hoping to get support and a permit, but received no clear response, perhaps due to the upcoming construction of a new school on the site, or having no one responsible for this informal space. Nothing happened and the garden continued on for months.

In July, with the garden in full bloom, the TDSB sent workers to clean up the site in preparation for construction, including the gardens. I knew it would happen at some point, but I biked down to the gardens, and was approached by a TDSB worker who felt just as disappointed as me. He didn’t want to remove it either, and in fact, all of the workers there that day had refused to. This incredible act of refusal (thanks to all of them for putting themselves on the line for a garden) bought me time to make a bit of a fuss, and get some answers about when construction was really starting. My goal was just to have the garden remain as long as possible before construction began. This resulted in people calling their local Councillor and TDSB Trustee, and in the writing of several news articles.

For me, the most wonderful thing about this time was that I saw that the community and the gardeners were even more passionate than I was about keeping this garden around. We had created something nice, and people had grown attached to it. Most of our other gardeners do not have access to land to grow on. Community members loved to see it, and loved it on principle. It was humbling to see how this little garden had grown beyond me. In practice, the space never belonged to me, the TDSB, or anyone else.

In the end, with local MPP Marit Stiles on board, the gardens were supported by the TDSB and allowed to continue for two more months before construction began. There were a few bumps in communication on the way, but it was as good an ending as anyone could expect. Bloordale Beach remained partially open during this time.

I had the rare opportunity to put my research into practice, experiencing first-hand how good use of land for the public can survive despite liability fears, lack of communication, and existing inflexible processes. We ended on a high note in September with a Final Harvest celebration with local musicians, badminton, a potluck, and more, before the site was secured for the construction to come. See more on Bloordale Beach Community Gardens here.

Local Musicians at Final Harvest (2021).

Harvesting the long awaited potato at Final Harvest (2021).

Lessons Learned

My major take-aways from interviewing informal growers and stewards for my paper, and then going on to organize an informal community garden this summer, are:

Local people have unique and valuable knowledge of the land around them, as well as a strong connection and motivation to care for this land (whether it's a park, a ravine, or an empty construction site!)

Their goals often align with or complement public goals for sustainability and community building, and

Often the only gaps between public landowners and informal growers/stewards are in communication and over-conservative approaches to dealing with liability.

Lowering the defences a little to these low-risk/high-benefit activities and sharing knowledge in both directions results in significant social benefits and practical gains, and I saw that was true with all the informal growers and stewards I interviewed, as well as our Bloordale Beach Community Garden this summer.

So many of us are disconnected from or lack access to nature. As planners and other professionals involved with place-based work, we need to approach community members who want to connect with the land as a valuable human resource, not a liability. Think about how you create and protect green spaces with people in mind, share knowledge about land use and sustainability goals in accessible ways, and consider how policy and programs can adapt to, and leverage, human connections to land.

Thank you to the excellent guidance of my MRP supervisor Victor Perez-Amado, and my insightful second reader Sheila Boudreau, Principal at SpruceLab.

Thanks also to all the cool Bloordale Beach gardeners for coming out on Mondays during a pandemic.