Why a Rare Urban Wetland Matters.

Small’s Creek has a wetland.

It is there, as it always has been.

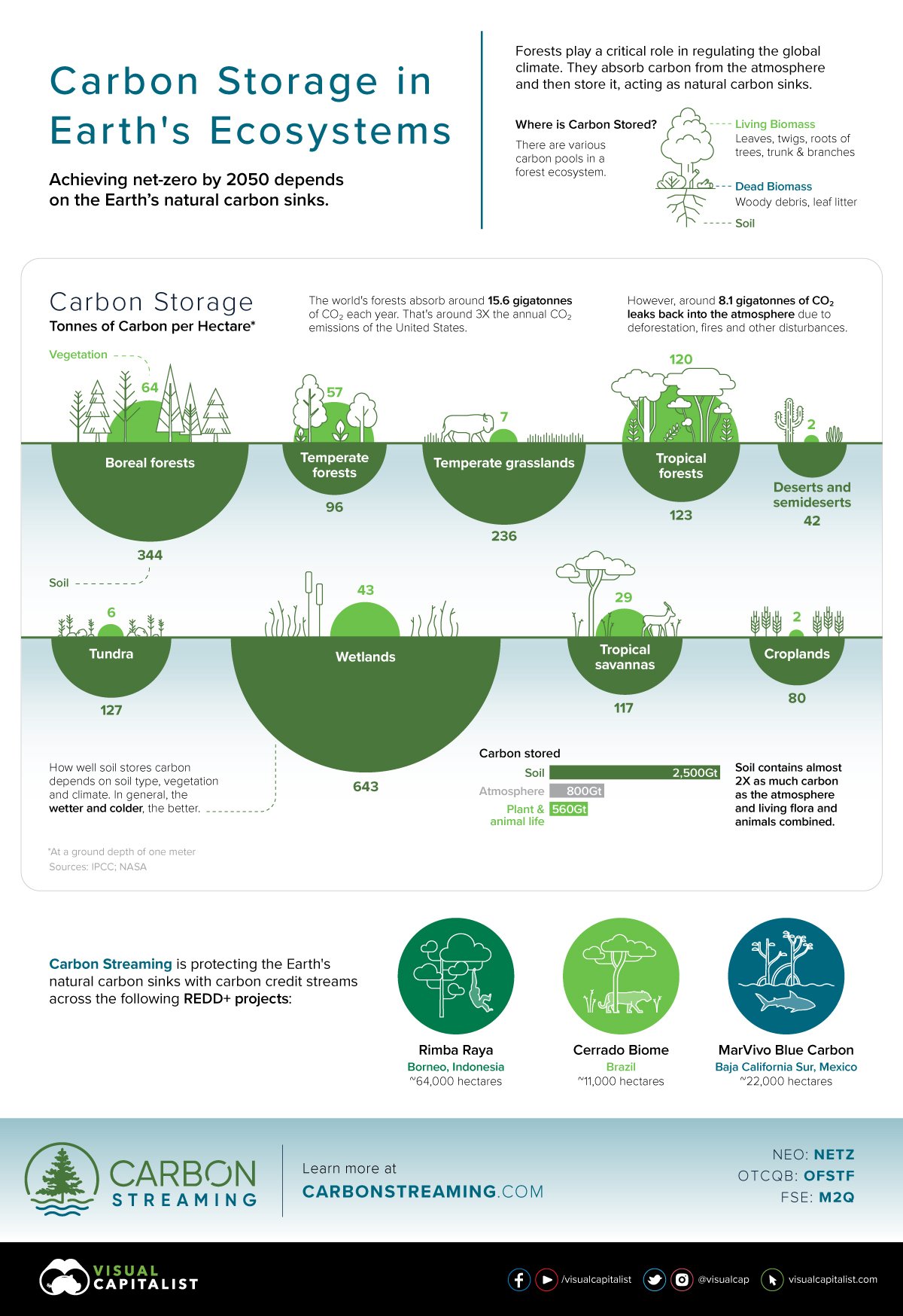

In his recently published book, Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation, influential economist and environmentalist Paul Hawken (2018) writes: “wetlands are extraordinarily valuable, the most diverse ecosystems on the planet, one of the two greatest vaults of terrestrial carbon” (Hawken, 2021). All wetlands, regardless of their size, classification, or condition, provide immeasurable environmental benefits to humans and other creatures. They support biodiversity (habitat, food, connectivity), improve water quality and hydrological functions (plants take up pollutants though their roots, and wetlands act as ground water recharge areas), increase the base flow of water bodies downstream, and decrease stormwater runoff temperature (improving aquatic habitat downstream). (See graphic depicting carbon storage of wetlands in comparison to other ecosystems, at end of blog: 643 tonnes of carbon per ha, and the wetter and colder the wetland, the better the wetland performance).

Why are urban wetlands so important?

In the highly urbanized areas of the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA), over 85% of original wetlands have been lost, making any wetland that remains a priority to protect and restore. It would be reasonable for the public to expect that any plans that could negatively impact a wetland would be treated with the utmost care and respect. Sadly, this has not been the case for Small’s Creek ravine and wetland, advocated for by the Friends of Small’s Creek, a local not-for-profit in the east end of Toronto. According to John Wilson, of Lost Rivers Toronto, Small’s Creek in this area is the last natural remaining remnant of a tributary in the east end of the city that originally flowed into what was Ashbridges Bay at Lake Ontario. As part of the Lakeshore East Rail Corridor Expansion project, Metrolinx (an agent of the Province of Ontario) has designed a railway expansion that removes many mature red oaks that shade, cool, and nourish the wetland, without taking the existing wetland into account. The Friends of Small’s Creek, are rightly concerned that because the wetland wasn’t classified until 2018 by the agency’s ecological consultants, required safety measures may not be in place for construction (protection against fuel leaks, spills and contamination, erosion and sedimentation control, and specialized drainage practices). Given the recent overuse of de-icing salt, spread over existing boardwalks in great quantities by Metrolinx contractors (which later had to be removed), this concern is valid.

At the time of writing, the active removal of these trees is underway in great haste, despite Toronto Council’s recent unanimous vote to pause this work until plans for an ecological restoration plan are finalized (see link to motion in Resources at end of blog). The consensus of several ecologists who have spoken to the Friends of Small’s Creek have confirmed that the loss of these trees, without proper and prompt ecological restoration being taken, will cause irreversible long-term damage to this rare urban wetland. The loss of the shade will change the microclimate conditions, and disrupt critical nutrient cycling provided by the trees themselves (through their root systems, and from fallen leaves), resulting in degraded growing conditions for plants and habitat loss for wetland creatures.

The interrelationships between wetland area trees, their unique soils, and the plants that have evolved there for millennia, are complex and impossible to recreate exactly. A fact that is widely accepted is that protecting, preserving and restoring wetlands is a sound investment as green infrastructure. This effort leads to decreased flood risk of local areas and properties downstream, improved biodiversity, and maintaining critical public realm assets that offer physical and mental health opportunities (e.g. passive recreation, and medicinal benefits from forest bathing, including cancer prevention). Degrading and damaging a forested wetland is risky business, for many reasons! As Dr. Sandy Smith (Director of Forestry Programs, University of Toronto) explains, “Green infrastructure and its critical role in ecological resilience has historically been undervalued. Once lost, it cannot be replaced. Whether it is the City’s ravines or wetlands, we must protect these natural treasures for future generations.”

A view of the Small’s Creek wetland in the fall, looking east.

What kind of wetland is at Small’s Creek?

In Ontario, wetlands are ranked, classified, and evaluated into four different types to inform land use planning, and to protect them and their benefits to society. Evaluation is done by ecologists trained in this work and is based on criteria related to groundwater storage and release, species at risk, and habitat provided for creatures. At Small’s Creek, a 2016 report documented the area as being a ‘Fresh-Moist Willow Lowland Deciduous Forest’. But in 2018, when a field investigation was undertaken, a second ecological study found the area to have a wetland that is classified as a ‘Deciduous Swamp’ (in the lowlands surrounding Small’s Creek), and a ‘Dry-Fresh Oak-Maple-Hickory Deciduous Forest’ on the valleyland slopes. While not consulted, the local community could have easily provided information about the year-round standing water, the abundance of wetland plant species (like marsh marigolds, jewelweed, and swamp aster), and the precious salamanders that live in the wetland. Needless to say, evaluating a site with a known waterbody, adjacent to a designated Environmentally Significant Area (ESA), by studying maps and data as a desktop exercise, fails to protect the environment and the public interest.

Ecologist and Professor, Dr. Stephanie Melles, of Ryerson University, describes the significance of the wetland at Small’s Creek in greater detail:

"All remaining wetlands in Ontario need protection. The removal of mature oak and hickory trees in Small's Cr will irreparably modify drainage and likely lead to increased initial flooding and longer-term loss of this rarest of rare wetland type (i.e., when things dry out over time and there are fewer to no mature trees to take up the excess water). All remaining wetlands in Ontario need protection. The removal of mature Oak and Hickory trees in Small's Cr will irreparably modify drainage and likely lead to increased initial flooding and longer-term loss (drying out) of this rarest of rare wetland type.”

Who lives in the Small's creek wetland?

The fragmentation and ongoing degradation of natural linkages is an increasing crisis in terms of supporting biodiversity, and allowing mammals to move through places that prioritize humans. At Small’s Creek, mammals (fauna) such as coyotes, foxes, rabbits, possums, raccoons and squirrels depend on the wetland and for food, water, habitat, and movement. Larger birds like raptors and communities of ravens roost in the tall mature trees, and depend on the wetland for food (prey) and water. It was only in the last ten years that ravens have been seen again in this area of Toronto, after being gone for decades. And songbirds like woodpeckers, blue jays, cardinals, chickadees, nuthatches and endangered bats also rely on the wetland for insects, water, and habitat as well. When cities remove these spaces, the local ecosystem becomes imbalanced. Without landscape connectivity, larger creatures are forced to move through human spaces to find food and shelter. Sightings of coyotes roaming local roads is common, as are stories of cats and small dogs being killed (thankfully no small children have been hurt, to date). Tiny salamanders are also found in the wetland, if you look patiently and closely. With the loss of the wetland, they will not survive.

An eastern red-backed salamander that lives in the Small’s Creek wetland. (Photo Credit: Polly VandenBerg, with permission from Friends of Small’s Creek)

Fox in a City of Toronto ravine ecosystem. (Source: City of Toronto)

A family of mallard ducks swimming in the water of Small’s Creek, winter 2022. (Picture credit: Cleo Buster)

Removing the many heritage red oaks at Small’s Creek is also a sad tale: long-lived and growing to a very large size, oak trees in particular support an incredible amount of biodiversity in a wetland ecosystem, from habitat, to food, to shade for the wetland to keep it from drying up from the rays of the hot sun. Douglas Tallamy refers to Oak as a “Powerhouse Keystone Species” that serves as a “lifeline for countless creatures.” Their abundant leaf litter falls on the wetland, decomposing and adding necessary nutrients to dozens of underground species, the water and the rich, dark wetland soil itself. Life giving life, in the incredible cycle of nature.

Natural trail along the south edge of Small’s Creek, in the wetland area.

Other plants (flora) that live in the Small’s Creek wetland depend on the shade, nutrients, and moisture / hydrological conditions for their survival too! The unique conditions provided here are the reasons that native plant species like marsh marigolds, watercress, jewelweed, swamp asters, zigzag goldenrod, are healthy and prolific here. Even eastern hemlock can be found! But when the water is gone, and the soil dries up, these plants will fail, along with all of the benefits that they provide.

On the humans that live in the Small’s Creek area, Helen Mills, Founder of Lost Rivers Toronto, has this to say: “We have held a few walks along the creek over the years, and I've seen that the local community is deeply connected with and has engaged in serious stewardship and care of the ravine for a long time. It is an important part of people's local identity and sense of place/ home and is deeply treasured. City staff too have worked hard to manage the forest in an appropriate way and that care shows.” And many of the residents within walking distance of this natural space rely on it as a source of passive recreation (approx. 20,000 people in that distance live in apartments without access to private yards, many of them families, children, and seniors, calculated using the 2016 census data and a 2.5km walking route). Over the past couple of years, Small’s Creek has become a preferred place to recharge emotionally given the stresses of living with the Covid-19 pandemic. Water is Life, and on a level that is woven into all of our DNAs and psyches, we know this to be true.

How does this wetland fit into the bigger picture?

Small’s Creek is a tributary that flowed directly into Ashbridges Bay, and TRCA recognizes it as part of the Don River Watershed due to its close proximity. The health of the Don River and its watershed has been a cause for concern for generations, and is central to the history of the founding of the City of Toronto (for more on this, read Reclaiming the Don: An Environmental History of Toronto’s Don River Valley, Jennifer L. Bonnell, 2014). In fact, Charles Sauriol, who inspired the conservation movement across Canada in the mid 1950’s, lived his whole life in the watershed and documented its degradation from urbanization in his many publications. This work led to the Metropolitan Toronto Region Conservation Authority, which later became the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority.

From 1989 to 2010, the community-based group Task Force to Bring Back the Don advocated for improved health of the Don River (publishing the book, Bringing Back the Don), and a City of Toronto Planner was even assigned to support this work. Recognizing the need to work in an integrated way across the many government agencies and other organizations across the Don watershed, in 2013 the TRCA formed the Don River Regeneration Council, which helped advance the steps noted in the celebrated document, 40 Steps to a New Don: The Report of the Don Watershed Task Force (1994). This document states three parts to the overall vision of a future healthy Don River, and includes guidance and concept plans to help guide the necessary changes and restoration that are needed to get there: Protect what is healthy; Regenerate what is degraded; and Take Responsibility for the Don.

Given the decades of studies and attention paid to the Don River area in Toronto, it’s shocking that the Small’s Creek wetland was missed in the earlier ecological assessment and review for Metrolinx’s plans and reports.

Creeks and tributaries that flow(ed) into the lost Ashbridge’s Bay, Toronto (Source: Lost Rivers Toronto).

A problematic issue common to urban creeks in the planning and engineering of cities is the perception that they are nothing more than part of the overall storm drain system. Thankfully, cities across the globe that buried their creeks and drained their wetlands to make room for development, are now seeing the failure in doing so. There are many examples of cities daylighting buried creeks, transforming them into loved public parks, while simultaneously improving landscape connectivity and biodiversity. This work is also being done to deal with the impacts of increased impermeable surfaces due to development (roads, parking lots, buildings, etc.) and the subsequent flooding that occurs. The existence of Small’s Creek as a natural creek with a wetland is nothing short of a miracle, and needs to be valued as one.

A wiser approach to designing resilient communities, advocated by the United Nations as ‘nature-based solutions’, is to create places that can adapt and respond to the increasing impacts of climate change, such as more frequent and intense rain storms, and extreme heat events. Living green or natural infrastructure cools cities through natural shade and evapotranspiration as moisture is released by leaves into the air. Designing urban areas with green infrastructure can increase above ground water storage area, cool stormwater runoff (decreasing thermal pollution, which degrades aquatic habitat downstream), and improve water quality (limiting sewage entering waterways due to overburdened combined sewer overflows in large rain events). Landscapes can become high-performing infiltration and bioretention areas with engineered systems that filter, clean, absorb and retain rain and stormwater runoff, holding it back from the overwhelmed storm drain system, resulting in cleaner water when it does reenter. The naturalization of the mouth of the Don River project is an example of engineering to help to deal with the mistakes of the past, as an ‘end of the pipe’ solution to filter and remove pollutants from the stormwater before it enters Lake Ontario (the city’s source of drinking water). An urban wetland like Small’s Creek is an incredible opportunity to educate the local community about their role in helping to protect and restore this unique ecosystem, as well as being an invaluable destination for environmental class field trips from local schools.

Small’s Creek c.1909 overlaid onto the street grid of that time. (Source: Lost Rivers Toronto).

How has Small’s Creek changed over time?

Thinking about the Don River, and the decades of work and massive investment being spent to naturalize the mouth of the Don River, inspires one to think about what Small’s Creek was like, before Europeans settled in the area. Chapter 1 in 40 Steps to a New Don describes in detail the geological history of the area, including that of the lower Don River. Rich with forests, streams, ponds and marshes, natural corridors provided places and linkages for Indigenous Peoples, as well as fish, birds, and other animals to live and move through. As described by the City of Toronto, the city is the Traditional Territories of the Mississaugas, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples, who all predate European settlers by at least 12,000 years (and First Nations Peoples have said that this timeframe is in fact much longer).

Image of an old military map of Toronto. (Source: Lost Rivers Toronto).

As settlers moved into Toronto, they cleared the forests for agricultural fields and housing, dramatically changing the natural heritage and hydrology of the city. To learn more about the settlement history of Small’s Creek, see the film created with John Wilson, called Small’s Creek: A Brief History (John was the Chair of the Task Force to Bring Back the Don, and involved with the original community group, Bring Back the Don). As John explains, the creek was named after the landowner, Charles Coxwell Small (c. 1870 – 1912), and the area was greatly changed when the railway line was constructed, severing the north end of Small’s Creek (the area this blog is focused on) with the ravine to the south (now called Williamson Ravine). In 1950, only 15% of the Don Watershed was urbanized! In John’s words:

“Now we realize that a ravine like this is really a precious thing. We’ve lost a lot. We’ve lost so much of our connection to our natural world. A lot of people are beginning to see that the continual decline, generation after generation, is not satisfactory. And there’s some momentum now for reversing some of the damage that’s been done. … How do we want to preserve a place like this ravine in a way that moves people along the railway line that doesn’t just clearcut nature.... Every little piece like this is going to add to a world that is still liveable for generations to come.” (from Chris Terry’s film Small’s Creek: A Brief History).

What are the plans for Small’s Creek now?

As the Friends of Small’s Creek continue their advocacy to pause the clear-cutting of mature trees by Metrolinx’s contractors, and City of Toronto staff work closely with local Councillor Brad Bradford’s office and TRCA to investigate what can be done, the need for a graphic that clearly shows what is planned for this area was identified.

The image below was created for a recent public meeting that involved all three levels of government, with elected officials stressing the need to pause work until a professional ecological restoration plan is created (with community involvement), and a timeframe and budget are established. Because the railway expansion may not happen until 2023, the risk of destroying the wetland by exposing it to full sun, without restoring the slopes and providing adequate shade, is real. The map shows the 4m wide access road through the wetland to reach the culvert (to be composed of compacted aggregate); the 400’ long, 9’m high concrete retaining wall; and the limits of the wetland area as classified by ecologists. The map also shows the existing natural trail on the south side of the creek as being removed, and is a trail that is quite possibly an Indigenous route that predates settlement.

(Source: Friends of Small’s Creek)

Why does a small urban wetland matter?

As Helen Mills shares: “I think of the fragmented creek system as a framework for reconceptualizing a future city in which the creeks and green spaces become a restored living matrix for a completely different way of living with nature and water in the city. So much work has been done in the past 20 years or more, yet I see that death by a thousand cuts continues.”

In the case of the Small’s Creek ravine and wetland, the process undertaken to plan for and design for a massive transit infrastructure project has demonstrated clear gaps in process, including with community engagement. If the local community had been engaged, the existence of the wetland and the existing path of travel with the natural trail would not have gone unnoticed. Comparing photos of the wetland from Metrolinx’s earlier reports to those of this blog post, in addition to the many that have been posted on Twitter by the Friends of Small’s Creek and other concerned members of the community, show that in even the seven years from then to now, that this deciduous swamp wetland, and all of its creatures, are resilient and alive.

What happens now is a pressing question for the decision makers involved to decide.

The Toronto Ravine Strategy, adopted by Council in January, 2020, states:

“Ravines are fundamentally natural spaces. Ecological function and resilience is the foundation for long-term sustainability of the ravines and watersheds. We are all guardians of these spaces and must treat them with care and respect. All actions related to ravines should be guided by the overarching goal of protecting these spaces by maintaining and improving their ecological health.” (City of Toronto, 2022)

And we know what the Don Watershed Task Force would say:

Protect what is healthy, regenerate what is degraded, and take responsibility for this creek and wetland.

Picture taken in 2001 of a 6 year girl standing in Small’s Creek wetland. (Photo Credit: Bruce Reeve)

Picture taken in 2019 of the same girl, now a 23 year woman, standing in Small’s Creek wetland. (Photo Credit: Bruce Reeve)

“Small’s Creek Ravine, otherwise known to my family as “The Ravine”, has been an anchor for me throughout my life. It’s one of the places I’ve missed most since moving out of the neighbourhood two months ago. As a child, Easter egg hunts were held here. “Want to take a walk through the ravine?” meant let’s go explore nature and slow down a little bit. The sound of the creek, the squishy mud path after a rainy day, and the immense greenery that surrounds you are a few of the things I cherish most about the ravine. Let’s give back to the ravine all it has given to us. Let’s protect what was and still is a small, local sanctuary to children, teens and adults alike.” - Oonagh Reeve, Posted on Instagram in 2022

NOTES:

The author wishes to honour the late Liza Ordubegian (who left us in 2015) with this blog post, a local community member and environmental advocate who inspired others through her work and generous spirit. Many may not know, but as an environmental consultant, Liza worked on many large-scale wetland classification projects, and would have been actively involved with the Friends of Small’s Creek if she were still with us today.

A Small’s Creek Lost Rivers Toronto tour is planned for March 20, at 2pm, and is open to the public (see invitation posted at the end of this blog).

Author:

Sheila Boudreau, BA, BLA, MA (Planning), OALA, CSLA, RPP/OPPI, MCIP, is the Principal of SpruceLab Inc., a Landscape Architect and Registered Professional Planner with over 25 years of experience (2011 - 2017 as an Urban Designer with the City of Toronto, and 2017 - 2019 as manager of the landscape architecture team at Toronto Region Conservation Authority). She teaches planning, design and green infrastructure courses at the University of Waterloo, Ryerson University (renaming underway), and previously, University of Toronto. Since 2017, Sheila has been on the Board of Advisors for the Urban Water Research Centre, and since 2015, has represented the Ontario Association of Landscape Architects on the Green Infrastructure Ontario Coalition. Early in her career she was a member of the Don Watershed Regeneration Council, following her Master’s thesis on community-based integrated planning for urban waterways. Sheila continues to support this work through her involvement on the Friends of Small’s Creek’s Technical Advisory Committee. She is grateful for the opportunity to live, work, and have raised her children in the Traditional Territories of the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Huron-Wendat Peoples, and tries to honour this privilege through offering environmental advice and advocacy to help protect and regenerate the Territories.

Contributors:

Dr. Stephanie Melles is a Professor at Ryerson University, and leads the Spatial Ecology Lab. She specializes in geo-spatial methods at the land-water Interface, and explores ecology not just on land or in water, but in both. By using this two-lens approach, her work contributes to a better understanding of interrelated issues and impacts of stressors in (urban) land-water ecosystems. The lab uses the tools of data science to research ecology, and spatial and geo-computational tools to search for patterns across multiple scales — from aquatic mesocosms to watershed macrocosms.

Helen Mills is a gardener, citizen geographer, eco-landscape designer, educator and social entrepreneur. She is the founder and co-director of Lost Rivers, a program of the Toronto Green Community that supports volunteer-guided place-based walks integrating stories and information around history, geography, environmental and urban issues. It is based on the concept of the Blue Green City, or a city that integrates water management and green infrastructure to recreate a naturally oriented water cycle and enhance natural habitats. The Lost River Walks are storytelling tours about the human and natural heritage of the city’s buried creeks, and the website is a field guide to many of the lost rivers.

Birgit Siber, Bach. Arch, OAA, FRAIC, LEED AP, is an emerging advocate for urban wilderness and regenerative environments. She has practiced architecture since 1987. She was a Principal with Diamond Schmitt Architects, where she worked for 23 years. Her guiding focus is in the arena of design, innovation and sustainability. In 2019 she was awarded the Sustainable Buildings Canada (SBC) Lifetime Achievement Award. Birgit currently serves on the Toronto 2030 District Advisory Board, as a member of the RAIC’s Committee of Regenerative Environments.

Resources:

Bonnell, Jennifer, L. (2014). Reclaiming the Don: An Environmental History of Toronto’s Don River Valley. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

City of Toronto Biodiversity in the City; and the Biodiversity Booklets

Friends of Small’s Creek and Williamson Ravine

Green Infrastructure Ontario Coalition

Hawken, Paul. (2021). Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation. (New York: Penguin Books).

Metrolinx maps and information: See page 43 for a map that shows Small’s Creek aquatic habitat assessment, followed by a report on flora and fauna (including mammals, reptiles, amphibians, aquatic species, fish and fish habitat, etc. See page 60 for a map on Aquatic Natural Heritage Features, TRCA regulation limits, and Terrestrial and Natural Heritage System. It shows just how urbanized the watershed is and how disjointed Small’s Creek is post development.

Port Lands: The New Mouth of the Don River, Waterfront Toronto

Province of Ontario, Wetland Evaluation

Sauriol, Charles. Wikipedia Page

Tallamy, Douglas W. (2021).The Nature of Oaks. (Portland: Timber Press Inc.)

Terry, Christopher. (2021). Small’s Creek: A Brief History (with John Wilson, Lost Rivers Toronto. (YouTube): Small's Creek is one of the last remaining creeks and ravines in the east part of the city of Toronto that drained into Ashbridge's Bay. This clip looks at the geological forming of the creek and the impact of colonial settlement and infrastructure development on it. With a rail line bisecting the last remnants of the creek, it is critical to try and preserve as much of this unique eco-system as possible. John Wilson, one of the leads of the Lost Rivers Project, guides us through this brief history.

Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, ‘Wetlands’

The Toronto Ravine Strategy (adopted by Toronto Council Jan. 2020)

United Nations Development Program, Issues Brief on Nature-based Climate Solutions, November 2020

‘Visualizing Carbon Storage in Earth’s Ecosystems’. Visual Capitalist, Jan. 25, 2022

Small’s Creek in the News:

Ken, Steph Wong. ‘The Line Between ‘Invasive’ and ‘Native’ Blurs’. The Local, June 25, 2022. Toronto’s Climate Right Now. A series about vulnerability and adaptation in Canada’s largest city, in collaboration with The Narwhal.

Draaisma, Muriel. ‘Metrolinx cuts down trees in 'ecologically significant' ravine despite local, city council outcry’. CBC News, Feb. 8, 2022

Marfo, Dorcas. ‘Trees came down in Small’s Creek Ravine Monday despite push for preservation’. Toronto Star, Feb. 8, 2022.

Siber, Birgit. ‘In My Opinion: Metrolinx needs to change it’s destructive plan for Small’s Creek and respect Toronto ravines’. Beach Metro News, Nov. 14, 2021.

UPDATE (Feb. 14, 2022): The image below is from a Friends of Small’s Creek member, documenting the heritage red oaks and other trees taken down by Metrolinx, ignoring the expressed request from Toronto City Council to pause work.

The images taken below are from mid-June, 2022. The mature oaks were all removed hastily, yet no work has been been happening on the site according to the local community.